Potential Harm in Music Therapy?

Have you ever heard music therapy described as “non-invasive”, “non-threatening”, or as a treatment with no side effects? In this AMTA-Pro podcast, our music therapy colleagues Brea Murakami and Daniel Goldschmidt discuss the topic of the potential for harm in music therapy, recognizing it has implications for music therapists in clinical, advocacy, educational training, and research realms. Although the AMTA and CBMT Scope of Practice acknowledge the potential for harm within music therapy practice, definitions of harm and ways of conceptualizing harm are few and far between in music therapy literature. After recognizing the need to acknowledge the potential harm, the podcast speakers talk about the need to understand, monitor, address, and prevent harm. They introduce the Music Therapy and Harm Model (MTHM), which provides a way of conceptualizing sources of harm in a music therapy session, and they discuss the possibilities for more specific research, education, and training about the topic of potential harm in music therapy sessions.

[display_podcast]

Music and Harm:

What We Know and What We Need to Know

AMTA-Pro Podcast ~ October, 2018

Brea Murakami, MM, MT-BC

Daniel Goldschmidt, MT-BC

Have you ever heard music therapy described as “non-invasive”, “non-threatening”, or as a treatment with no side effects? These incorrect assumptions that music is innocuous at worst are troublesome. If we ignore the possibility that music interventions can be harmful or that a client may become distressed during a session, then we cannot begin to remediate harm with it happens. Although the AMTA and CBMT Scope of Practice acknowledge the potential for harm within music therapy practice, definitions of harm or ways of conceptualizing harm are few and far between in music therapy literature.

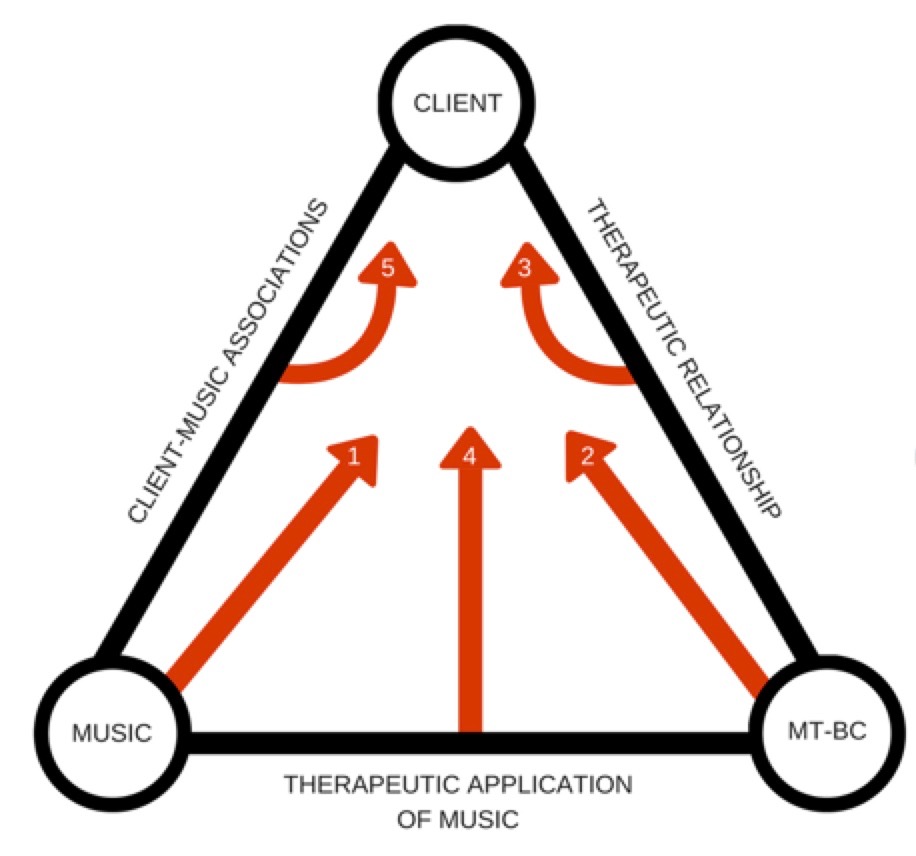

This podcast introduces the Music Therapy and Harm Model (MTHM), which aims to provide a way of conceptualizing sources of harm in a music therapy session. The MTHM visualizes three core components that are present in every music therapy session: the client, the music, and the music therapist. In addition, three interactions link these components: the therapeutic relationship (between the client and music therapist), the therapeutic application of music (between the music therapist and the music), and client-specific associations with the music (between the music and the client). Five of these elements are theorized to be sources of harm: 1) the music, 2) the board-certified music therapist, 3) the therapeutic relationship, 4) the therapeutic application of music, and/or 5) client-specific associations with the music. If harm occurs within the session, these same five elements should be responsive to the client’s needs and appropriately coordinated by the music therapist to reduce or lessen distress. In this way, we can also understand the unique protective factors within music therapy. This discussion also reviews the advocacy, educational, and research implications of the MTHM, as well as future directions for studying this important topic. As of the release of the October, 2018 release of this AMTA-Pro podcast, the manuscript for the Music Therapy and Harm Model (MTHM) has been submitted for publication.

Five Key Takeaways

Acknowledging the potential for music interventions to cause physical and/or psychological harm has important professional implications for music therapists that extend to advocacy and educational training domains.

Currently, definitions of harm and methods of conceptualizing harm pertaining to music therapy practice are very sparse and sporadic.

The Music Therapy and Harm Model (MTHM) theorizes that harm can arise from five potential sources during the music therapy session: 1) the music, 2) the board-certified music therapist, 3) the therapeutic relationship, 4) the therapeutic application of music, and/or 5) client-specific associations with the music.

The same five elements of the MTHM can become protective factors to mitigate harm if they are appropriately responsive to client distress during a music therapy session.

Self-awareness and a willingness to seek out supervision for challenging clinical experiences is the first step for music therapists to acknowledge potential instances of harm in their own practice.

Music Therapy and Harm Model (Image)

References

Barlow, D. H. (2010). Negative effects

Dimidjian, S., & Hollon, S. D. (2010). How would we know if psychotherapy were harmful? American Psychologist, 65(1), 21-33.

Gardstrom, S. C. (2008). Music as a noninvasive treatment: Who says? Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 17(2), 142-154.

Gattino, G. S. (2015). Some considerations about the negative effects of music. Musica Hodie, 15(2), 62-72.

Hatfield, D., McCullough, L., Frantz, S. H. B., & Krieger, K. (2010). Do we know when our clients get worse? An investigation of therapists’ ability to detect negative client change. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 17, 25-32.

Isenberg, C. (2012). Primum nil

Jonsson, U., Alaie, I., Parling, T., & Arnberg, F. K. (2014). Reporting of harms in randomized controlled trials of psychological interventions for mental and behavioral disorders: A review of current practice. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 38, 1-8.

Ladwig, I., Rief, W., & Nestoriuc, Y. (2014). What are the risks and side effects of psychotherapy? Development of an inventory for the assessment of negative effects of psychotherapy (INEP). Verhaltenstherapie, 24, 252-264.

Linden, M. (2013). How to define, find and classify side effects in psychotherapy: From unwanted events to adverse treatment reactions. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 20, 286-296.

Marik, M. & Stegemann, T. (2016). Introducing a new model of emotion dysregulation with implications for

Rheker, J., Beisel, S., Kraling, S., & Rief, W. (2017). Rate and predictors of negative effects of psychotherapy in psychiatric and psychosomatic inpatients. Psychiatry Research, 254, 143-150.

Roskam, K. S. (1993). Cluttering the psychological house: The damage music can do. In Feeling the sound: The influence of music on behavior (pp. 49-61). San Francisco, CA: San Francisco Press, Inc.

About the AMTA-Pro podcast speakers

Brea Murakami, MM, MT-BC is a board-certified music therapist and the clinical coordinator for Pacific University’s music therapy program near Portland, Oregon. She recently completed her master’s degree in music therapy at the University of Miami where she served as an academic supervisor and research assistant. Her clinical experiences include dementia care, neurorehabilitation, medical settings, and behavioral health. Brea is interested in bridging the fields of music therapy and music science through translational research. She also writes the blog “I’m a Music Therapist” and hosts the Instru(mental) podcast, both of which focus on sharing music cognition research with general audiences. Brea has spoken about her research and other topics at numerous international, national, and regional conferences. Brea’s Twitter: @BreaMTBC

Daniel Goldschmidt is a board-certified music therapist, business owner, and public speaker. He is currently studying for his master’s in music therapy with a graduate certificate in gender, power, and difference at Colorado State University. In 2015, Daniel started his entrepreneurial journey with Goldschmidt Music Services, LLC, which offers high-quality music therapy for central Virginia utilizing the talents of five board-certified music therapists. His practice currently focuses on people of all ages with developmental disabilities, and older adults with dementia-related disorders. Daniel is an avid speaker on Music Therapy and music cognition. Notably, his speaking engagements include a TEDxRVA talk, a keynote speech at the Virginia Occupational Therapy Conference, an upcoming TEDx talk with TEDxMILEHIGH in Denver, an upcoming keynote for the Virginia Association of Licensed Child Placing Agencies (